Is Your Property Landlocked?

“Landlocked.” The very word strikes terror in the hearts of property owners. A property that is landlocked is one that has no legal means of access. And without access, except perhaps by boat or helicopter, the property is rendered virtually unusable. In this article I will attempt to explain how one can determine whether property is landlocked, and if so, what can be done about it.

Our current state and local land use and subdivision laws do a pretty good job of insuring that every “legal lot” has a means of access. If the property that you own was legally platted or involved in a “boundary line adjustment” through your local planning department within the past 20 years or so, it is unlikely that you have an access problem. However, properties that were subdivided earlier than that, and/or without much governmental review or regulation, sometimes have access problems.

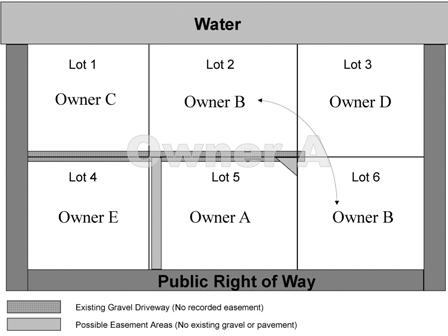

Figure 1, below, illustrates just one of several different scenarios in which property can become landlocked. In this hypothetical scenario, Owner A once owned property that he divided into six un-platted lots (Lot 1 – Lot 6). Owner A then sold five of those lots to various parties, and retained one lot (Lot 5) for himself.

Figure 1

In this illustration, Lot 2, owned by Owner B, is landlocked. Although there is a convenient and well-maintained gravel driveway that appears to provide access to Lot 2, in fact the driveway was created “informally” and there does not exist any easement for the driveway over the land owned by Owner C and Owner E. This might become a problem for Owner B if Owner C and Owner E ever decide to reclaim their property and to prevent its use as a driveway. Or there might not be any problem until Owner B attempts to sell or refinance Lot 2, at which time the prospective buyer or lender will probably not be willing to inherit this situation. In such cases, Owner B will need to attempt to obtain access by one of the following means (listed roughly in order of increasing difficulty and expense):

Negotiate an Easement with Owner C and Owner E. Owner B can attempt to reach agreement with Owner C and Owner E for a driveway easement over portions of Lot 1 and Lot 4 (where the current gravel driveway is now located). To be effective, the easement agreement must be (a) in writing, properly drafted to include the usual and necessary easement provisions, (b) signed by Owner C and Owner E, (c) acknowledged (i.e., “notarized”), and (d) recorded in the County Auditor’s office.

Negotiate an Easement with Owner A. For reasons discussed below, Owner B can likely force Owner A (from whom Owner B bought Lot 2) to provide access to Lot 2, over Lot 5, if necessary. See the areas in Figure 1 labeled “Possible Easement Areas.” This gives Owner B some bargaining leverage to negotiate with Owner A for a voluntary easement, over an agreed portion of Lot 5. If Owner B owns only Lot 2, then Owner B will probably need a strip at least 10 feet wide, across the entire depth of Lot 5. In the unusual situation that Owner B owns Lot 2 and Lot 6, then Owner B might need (at least in the short term) only a small, triangular area sufficient to “connect” Lot 6 to Lot 2. But if Owner B ever wishes to sell Lot 2 or Lot 6 separately, then Owner B will have to create an additional easement (not illustrated) over Lot 6.

Sue to Establish a “Common Law Way of Necessity”. If Owner B can prove in court that that Owner A (who once owned all six lots) deeded Lot 2 to Owner B (or any prior owner of Lot 2), without also deeding to that owner a means of legal access to and from Lot 2, then the court might grant to Owner B a “common law way of necessity”, which might be over the existing gravel driveway, or which might be over Lot 5 (the remaining land owned by Owner A). See the areas designated in Illustration 1 as “Possible Easement Areas.” If the court grants an easement over Lot 5, the location and configuration of that easement depend on several criteria that are within the discretion of the court and might vary depending upon the factual circumstance (e.g., whether Owner B also owns Lot 6).

Sue for “Condemnation of a Private Way of Necessity”. The Washington legislature created a “consolation prize” for owners who are in the situation of Owner B, but who are unable to establish a “common law way of necessity”. Such owners can sue Owner A (and/or other owners of lots surrounding Lot 2) under RCW 8.24.010 for a “private way of necessity.” This statute operates much like a government condemnation under power of “eminent domain” (e.g., when the government takes land to build new public roads). And, like the government condemnation, the private party exercising this power (Owner B) must compensate the affected land owner (Owner A) for the land that is effectively taken from the affected land owner to create the new easement. Because Owner B must pay Owner A for the a private way of necessity (in addition to court costs and attorney’s fees), it is usually (but not necessarily) less expensive for Owner B to establish a common law way of necessity. The decision in any particular case is fact specific, and depends upon (among other things) the strength of Owner B’s case for a common law way of necessity.

Sue to Establish an “Easement Implied by Prior Use” or a “Prescriptive Easement”. If Owner B can prove in court that the gravel driveway has long been in use by the owner of Lot 2, without the consent of the owners of Lot 1 and Lot 4, and under a claim of right by the owner of Lot 2 (i.e., the owners of Lot 1 and Lot 4 were not just being “neighborly”), and if Owner B can prove certain other elements of an implied easement (the details of which are beyond the scope of this article), then Owner B might be able to obtain a judgment awarding Owner B an “easement by prescription” or “easement implied by prior use” over the area currently occupied by the gravel driveway. However, prescriptive easements are not favored by the Washington courts, the burden of proving each element is upon the landlocked owner, and it is rare that a landlocked owner can actually establish one.

If Owner B is successful in obtaining access by any one of these methods, that means of access will usually be deemed “appurtenant to” Lot 2, and can be used and enjoyed by future owners of Lot 2.

The alternatives discussed above are specific to the hypothetical scenario that I have described, for purposes of illustration. As I mentioned earlier, there are also other forms of access problems. For example, if we change the hypothetical facts by making Owner A the current owner of Lot 2, and Owner B the current owner of Lot 5 (i.e., Owner A has “painted himself into a corner”), several new legal principles come into play. A discussion of this new hypothetical, and other examples of access problems, probably warrant a separate article. In any case, I will not attempt to analyze this situation here.

Note that all of the various implied easements must be established by a court in order to be valid and enforceable. Litigation is expensive, and the outcome is seldom completely predictable. In addition, Washington law is a bit murky and inconsistent in the area of implied easements. For these reasons (in addition to maintaining good relations with the neighbors) the parties are almost always better off resolving an access problem though negotiation and voluntary agreements. In situations that are somewhat contentious, it is sometimes a good idea to attempt mediation. Regardless of how the access problem is resolved, I highly recommend that each party be represented by an attorney with experience in real estate matters. Mistakes in this area can sometime take years to discover, during which time the problem can intensify and the stakes can increase.

Please remember that this article contains only the most basic information about its subject matter. I do not intend this article to contain detailed legal advice specific to any particular person or situation. Before entering into any agreement concerning your property, I urge you to consult with a real estate lawyer and with your tax or estate planning advisor.